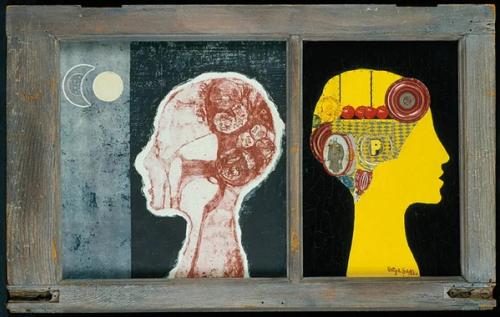

Religion and art, although suffering a tense relationship, are soul mates. In earlier days when making a living at advanced art was less conceivable, it was not uncommon for creative souls to speak of a “calling,” as a religious novitiate would. Van Gogh turned to painting only after failing the entrance exams to study theology. Kandinsky, regarded by some as the “inventor” of abstract art, mapped out its principles in Concerning the Spiritual in Art. It was said Lee Krasner thought of art the way she thought of God. Betye Saar, throughout her seven-decade career, creates dream-like assemblages based on “inexplicable feelings guided by the energy they hold.”2020Visions sees imagination as a lever for global change. There is an ineffable “something” in the imagination — some spark, defying words — a “something” that is shared by both art and religion. Union Theological Seminary was a partner with 2020Visions from the outset. When asked why, Serene Jones, its President and Johnston Family Professor for Religion and Democracy, remarks, “We are at a turning point in history. The world is cracking open. The spirit and power of art is standing in that rubble, with enormous opportunity, but also, to be quite frank, an enormous call. I find often with the artists that I have worked with, the resonance around this commitment to making the unseen seen and bringing forth the unimaginable into the space of the imagined so that we can live better, is absolutely crucial.”

Despite having “seminary” in its name, Union is recognized among many New Yorkers as a beloved local institution, almost outside a religious context, along the lines of the New York Society for Ethical Culture, Columbia University (its neighbor and partner) or the Metropolitan Museum of Art. And just as we at 2020Visions seek to craft problem-solving strategies for society through artistic vision, combining impulses, so too, does Union bring liberal Christian principles to bear on social justice challenges, with a history of influential thought in the avant-garde of theology and education.

To read about Union’s connection from its 1836 beginnings to social justice, notably the Abolitionist Movement, continue here.

L: James Memorial Chapel. With no fixed pews or permanent pulpit, the space changes each day to accommodate a wide variety of worship traditions and liturgical seasons. (Union Theological Seminary) R: The Quadrangle, Union Theological Seminary, New York, NY. (Courtesy of the Burke Library Archives)

Union has had a long history of notable faculty – renowned thinkers past and present including Paul Tillich, Reinhold Niebuhr (author of the Serenity Prayer), contemporary philosopher/activist Cornel West, foremost Black liberation theologian James Cone, anti-Nazi dissident Dietrich Bonhoeffer, feminist ethicist Beverly Wildung Harrison, womanist theologian Delores S. Williams, and Jungian theologian Anne Ulanov.

Dr. Jones, a leading scholar, public intellectual, and feminist, has led Union since 2008; under her stewardship, this mission continues to expand and deepen, the institution now housing Center for Earth Ethics led by Karenna Gore. It has allied itself with Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II and Rev. Dr. Liz Theoharis, co-chairs of the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival, among other progressive initiatives. Its current faculty includes Rev. Dr. Kelly Brown Douglas author of Stand Your Ground: Black Bodies and the Justice of God and visiting faculty Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow. It is just as apt to give seminars in Native herbal plant collection and the ethics of artificial intelligence as it is to focus on the Eucharist or principles of Church history; it teaches Buddhism and Islam in an interreligious engagement program alongside progressive Christian religions.

Union has had a long history of notable faculty – renowned thinkers past and present including Paul Tillich, Reinhold Niebuhr (author of the Serenity Prayer), contemporary philosopher/activist Cornel West, foremost Black liberation theologian James Cone, anti-Nazi dissident Dietrich Bonhoeffer, feminist ethicist Beverly Wildung Harrison, womanist theologian Delores S. Williams, and Jungian theologian Anne Ulanov.

Dr. Jones, a leading scholar, public intellectual, and feminist, has led Union since 2008; under her stewardship, this mission continues to expand and deepen, the institution now housing Center for Earth Ethics led by Karenna Gore. It has allied itself with Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II and Rev. Dr. Liz Theoharis, co-chairs of the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival, among other progressive initiatives. Its current faculty includes Rev. Dr. Kelly Brown Douglas author of Stand Your Ground: Black Bodies and the Justice of God and visiting faculty Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow. It is just as apt to give seminars in Native herbal plant collection and the ethics of artificial intelligence as it is to focus on the Eucharist or principles of Church history; it teaches Buddhism and Islam in an interreligious engagement program alongside progressive Christian religions.

— Wassily Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art

Tillich, who taught from 1933 to 1955 at Union, was one figure who could bridge the world of contemporary art and Christian faith. While delivering a famous talk at the Museum of Modern Art he observed, “an apple of Cezanne has more presence of ultimate reality than a picture of Jesus by Hofman.” Avant-garde visual art has its own manner of speaking about Absolute Truth — potentially as transporting as the raptures of St. Teresa. It is not meant to “illustrate” spiritual ideas, but to embody them — and for those not familiar with its rebellious ways, this can be challenging — like a Zen Koan.

And in our present world, the spark of spirit can be daunting to capture in words — a fire that even singes. Artist AA Bronson, co-founding director of Union’s Institute of Art, Religion and Social Justice from 2009 to 2012, has pointed out that the art community, while comfortable identifying with Tibetan Buddhism, is less so with Western religions as Judaism -- not to mention Christianity: “there are many, many artists who would declare themselves as spiritual but don’t really know what to do with that.”

Yet, perhaps this social turmoil, generating an inner hunger, may be exactly the condition opening the door to a new type of discussion. How can we find what is valuable in both worlds?

Carey Lovelace

Listen: Dr. Serene Jones and Carey Lovelace on “The Imagination in Religion and Art.”

(Music by Derrick Spiva)

Further Reading

Bashkoff, Tracey R. Hilma Af Klint: Paintings for the Future. New York: Guggenheim Museum, 2018.

Fanning, Leesa, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Encountering the Spiritual in Contemporary Art. Kansas City: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2018.

Fu-Kiau, Kimbwandènde Kia Bunseki. African Cosmology of the Bântu-Kôngo: Tying the Spiritual Knot : Principles of Life & Living. Athelia Henrietta Press; 2nd edition, 2001.

Kandinsky, Wassily. Concerning the Spiritual in Art. Translated by M. T. H. Sadler. New York: Dover Publications, 1977.

Thompson, Robert Farris. Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art & Philosophy. Vintage Books, 1984.

Tillich, Paul. “Art and Ultimate Reality.” Lecture (1959). In On Art and Architecture. New York: Crossroad, 1989.

Tuchman, Maurice, Judi Freeman, and Carel Blotkamp, eds. The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985. New York: Abbeville Press, 1986.

Fanning, Leesa, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Encountering the Spiritual in Contemporary Art. Kansas City: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2018.

Fu-Kiau, Kimbwandènde Kia Bunseki. African Cosmology of the Bântu-Kôngo: Tying the Spiritual Knot : Principles of Life & Living. Athelia Henrietta Press; 2nd edition, 2001.

Kandinsky, Wassily. Concerning the Spiritual in Art. Translated by M. T. H. Sadler. New York: Dover Publications, 1977.

Thompson, Robert Farris. Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art & Philosophy. Vintage Books, 1984.

Tillich, Paul. “Art and Ultimate Reality.” Lecture (1959). In On Art and Architecture. New York: Crossroad, 1989.

Tuchman, Maurice, Judi Freeman, and Carel Blotkamp, eds. The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985. New York: Abbeville Press, 1986.

Sacred Spaces

Atheneum, New Harmony, IN. (photo: M J Hanson)

New Harmony was a 19th-century utopian community founded by industrialist and social reformer Robert Owen — which failed two years after it began. In the 1950s, Jane Blaffer Owen came to re-settle New Harmony harboring goals of revitalizing the community with a vision of social equity. It became known as a center for advances in education and scientific research. In 1960, Philip Johnson’s Roofless Church was dedicated, an open-air non-denominational church and public space, commissioned by Owen as one of her modern additions to New Harmony’s vision of social equity and spirituality, an open-air structure where the only roof large enough to encompass a world of worshippers was the sky. Owen’s interest in the spiritual also led her to commission Richard Meier to design the much more ambitious Atheneum, near the banks of the Wabash River, completed in 1979, a modernist “cathedral” clad in porcelain, steel and glass, whose ramps, vistas, and framed views create an experience allowing for spaces of contemplation.

Dwan Light Sanctuary. (photo: Radius Books)

The Dwan Light Sanctuary, designed by art collector Virginia Dwan, earth artist Charles Ross and architect Laban Wingert, opened in 1996 on New Mexico’s United World College. Adorned with six large prisms mounted in sloping windows to capture light rays from sunrise to sunset, the orientation, and geometry of the building are derived from its alignment to the sun, moon, and stars. Its ribbons of pure color move with the revolving of the earth. A third apse, facing north, houses a window that frames trees and sky during the day and the North Star at night. The lunar spectrum can be seen on full moon nights. Visitors often meditate on the projections of color and light passing through the artfully created interior space.

Theaster Gates, Black Vessel for a Saint, 2017. (photo: Walker Art Center)

“A big part of my practice has always been concerned with the idea of the sacred. Both the kind of formal sacred, like organized religion or tribal participation, and the idea of sacred literature and language around the eternal or the invisible. While studying religion in college and having a life that was concerned with the world you couldn’t see, I learned how religious music and sacred texts inform people’s everyday. I’m always looking for messages about how the world works through those things.” –Theaster Gates

Theaster Gates’s Black Vessel for a Saint (2017) is a 20-foot architectural sculpture located in the Walker Art Center’s Sculpture Garden in Minneapolis, MN. The structure serves as an open-air, secular public sanctuary for Minneapolis. The exterior is composed of custom-made black bricks, created by grinding down and reusing salvaged bricks, that symbolize black entrepreneurship. Inside the structure is a life-size sculpture of St. Laurence, patron saint of archivists and librarians (salvaged from the demolished Church of St. Laurence in Gates's own south Chicago neighborhood). Black Vessel for a Saint functions as a meditative space, placed near other similarly meditative structures in the sculpture garden that calls for visitors to pause, reflect, and meditate.

Tadao Ando, Hill of the Buddha, 2015 (photo: Tadao Ando Architect & Associates)

"I begin every project with a hand sketch. In this modern age of computers and technology, architects and designers must rely on their instincts and the power of the human imagination. Architecture is at a tipping point where humans are becoming less necessary in the design process.” –Tadao Ando

Hill of the Buddha (2015—Sapporo, Japan) was designed by self-taught architect Tadao Ando who creates modern sacred spaces for 21st-century citizens by searching for the hidden balance between humans, nature, and place. The site is located on a gradually sloping hill on an expansive swath of land in the Sapporo countryside. The structure surrounding the Buddha sculpture was designed to create a long approach leading to the Buddha, which is not visible from the outside. Visitors enter through a concrete tunnel and are led to the 44-foot Buddha. When the hall is reached, visitors look up at the figure, whose head is encircled by a halo of sky at the end of the tunnel. The hill that tops the structure is covered with 150,000 lavender plants that transition from fresh green in spring to pale purple in summer and silky white with snow in winter.

Are there moments when a coincidence, and epiphany — or a state of grace — affected your life? Did they change you?

Betye Saar, The Phrenologer's Window, 1966. Assemblage of two-panel wood frame with print and collage. Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, LLC, New York, NY. © Betye Saar